Religion is not at the center of our family life, even though it was when my wife and I were kids. She attended a Catholic girls’ school, her grandfather was a deacon in the Church, and she has many stories about reenacting communion at home, but with white chocolate discs in place of communion wafers.

While she was learning from nuns, I was spinning nuns on a dreidel. My house was suffused with cultural Judaism -- all the holiday knick knacks, “Seinfeld” banter, and Bar Mitzvah prep. I was one of those youth-group kids who felt most at home while far from home, attending weekend-long conclaves filled with prayer, singing, and furtive glances. And if all that weren’t enough, my grandmother, who was a Holocaust survivor, lived in the house with us. You don’t say no to Nana.

But as the country drifted away from organized religion, so did my wife and I. Neither of us now belong to a congregation, pray, or center God in our lives. The values linger, but the dogma does not.

Yet we’re raising the kids to be Jewish. I could articulate why, but do the reasons really matter? Ultimately, these things are ineffable. It’s what feels right, therefore we’re going to do it.

But what is “it,” exactly? We’re a mixed household, but our mix isn’t really Judaism and Catholicism; it’s Judaism and secularism. How do we build a family that is inclusive of our values without giving priority to some over others?

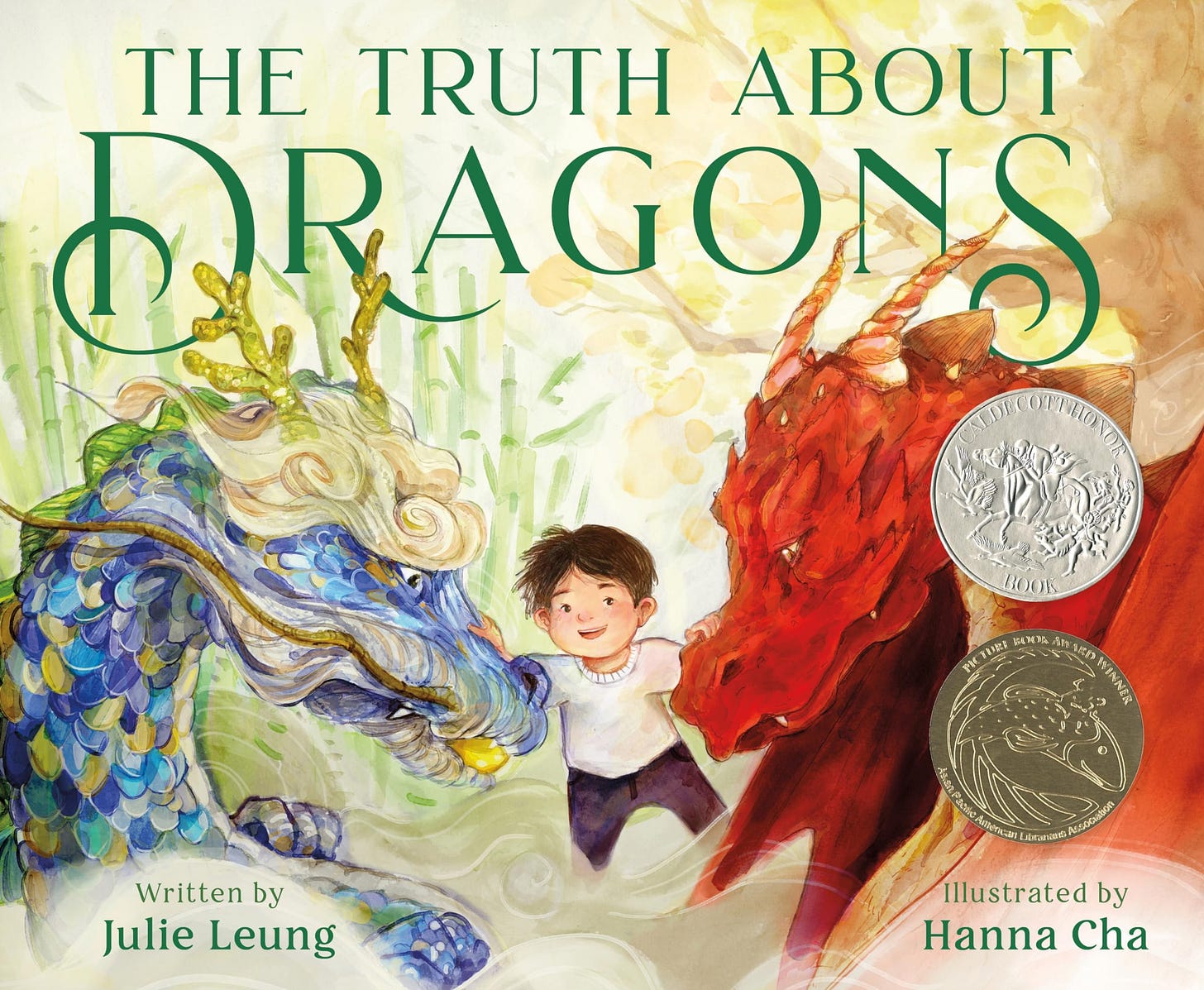

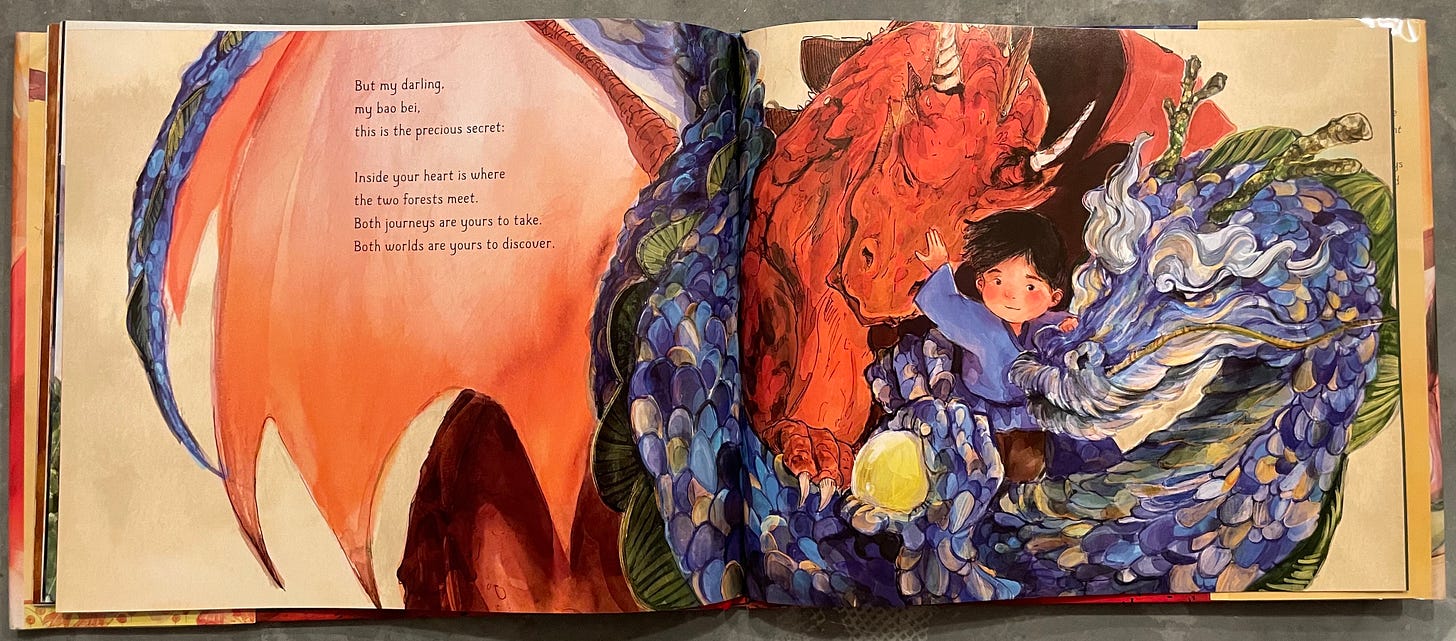

Some answers lie within “The Truth About Dragons,” a tender, mythical book by Julie Leung and illustrated by Hanna Cha with beautiful intention. The book has nothing to do with Judaism -- or any religion -- but its story will resonate with any mixed family, no matter the blend. It’s a reminder that you can have it both ways, and that doing so is its own way forward.

Our protagonist is known to us only as bao bei, a kid who’s getting a special bedtime story about the magic that lives inside him. But as his mom tells him, “In order to understand this magic, first you must go on an epic quest to learn the truth about dragons.” Dragons, plural.

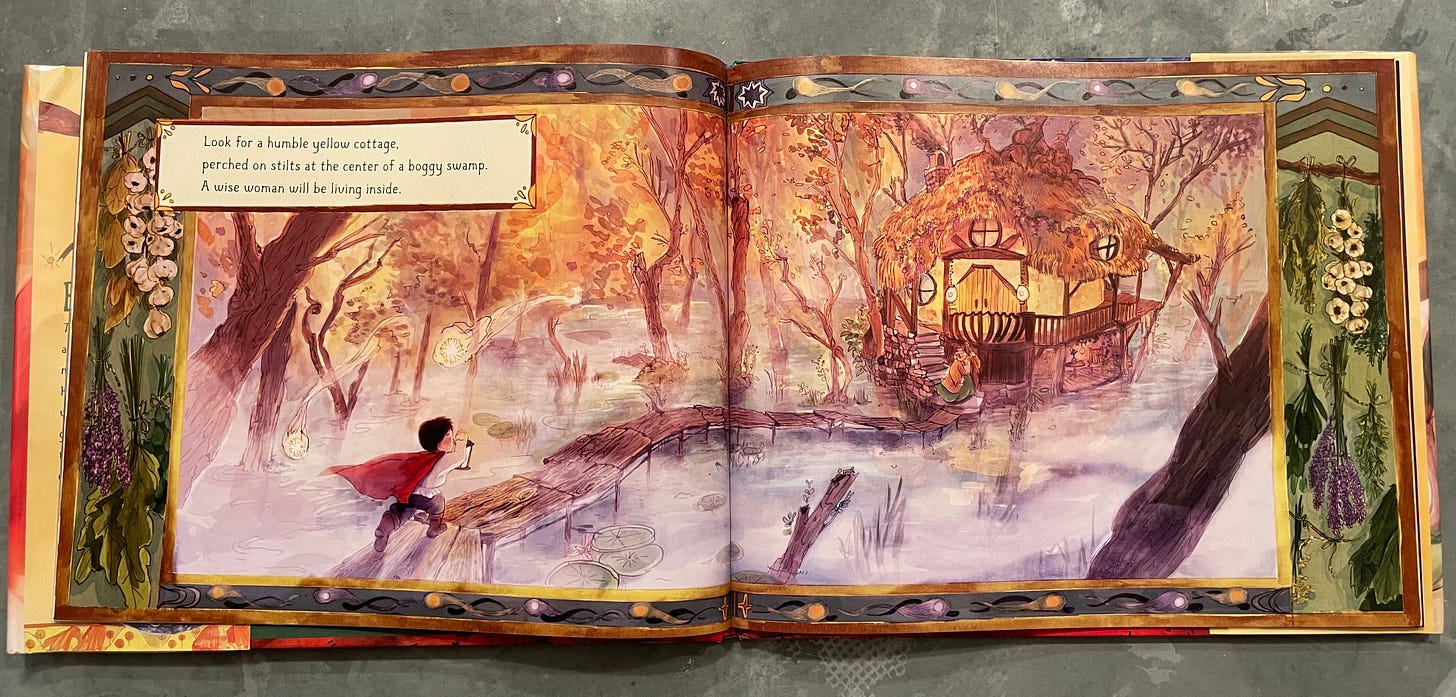

First, he treks through a Tolkienesque forest, filled with “gnarled groves” and “mischievous hobgoblins who peer at you from under mossy bridges demanding trinkets or answers to riddles.” Get past the hobgoblins and the will-o’-the-wisps and he’ll find a “humble yellow cottage, perched on stilts at the center of a boggy swamp.”

There, a wise woman awaits our young traveler. She takes him inside and reveals a cottage out of a fantasy novel. A cauldron bubbles over an open fire. Plants dry from the ceiling. A broom made of twigs rests in the corner.

When bao bei asks her about dragons, she is ready to share what she knows.

Her dragons are the stuff of Western fairy tales. All violence and greed, they are things to be feared. “Many a foolish knight has failed in their pursuit of a dragon’s gold and fortune.”

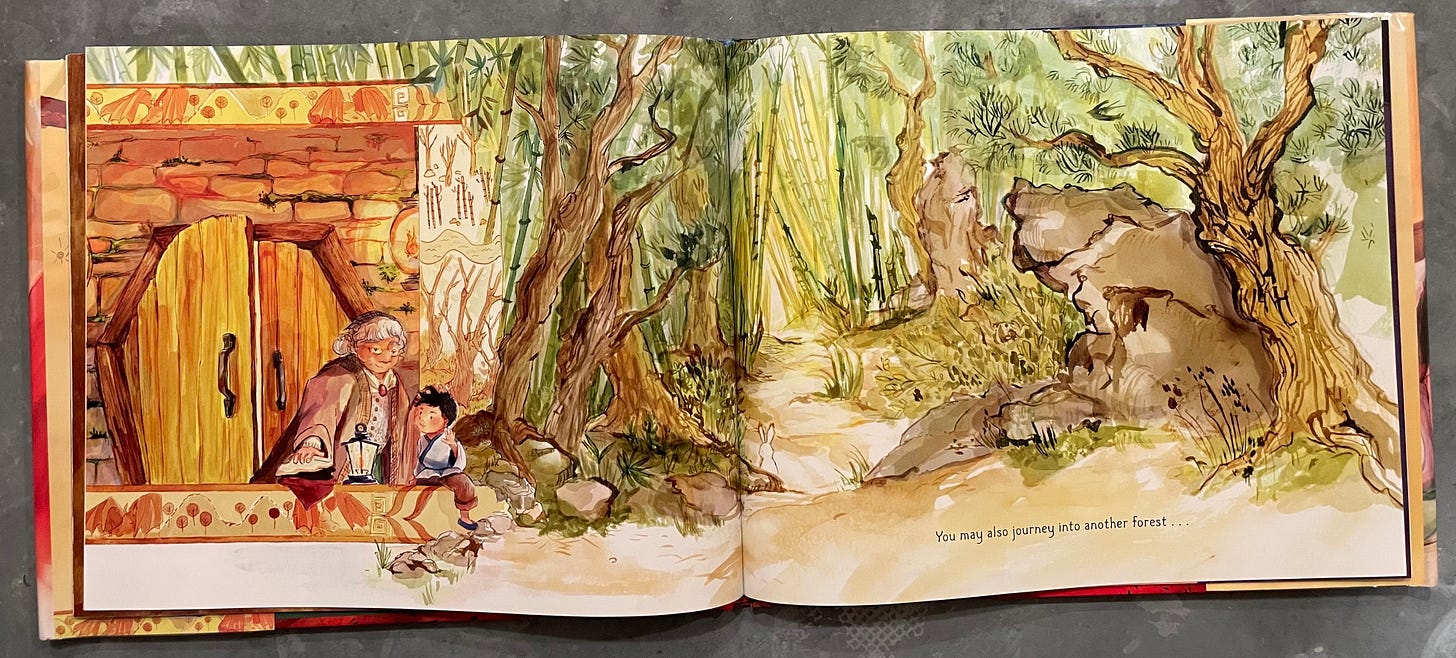

But there is more than one truth about dragons, and bao bei’s quest isn’t complete until he discovers another. So he leaves the woman behind and ventures into another forest. As he does, the illustrations shift from a more precise, gold-hued style to a cool, watercolor palette.

Bao bei’s look changes too, taking on the softer style of his new surroundings. This forest is “one of towering green bamboo, cracking and swishing in the breeze.” Nine-tailed foxes are leaving their footprints on the path, and lunar rabbits can help get bao bei back on track if he gets lost.

Again, there is a wise woman waiting, this time in front of a bilateral palace tucked inside a mountain valley. Her house has none of the homey clutter of the last woman’s. Instead, it’s filled with ornate vases and circular doorframes. “In a sitting room that smells of incense and jasmine rice, she will serve you chrysanthemum tea in a delicate porcelain bowl.”

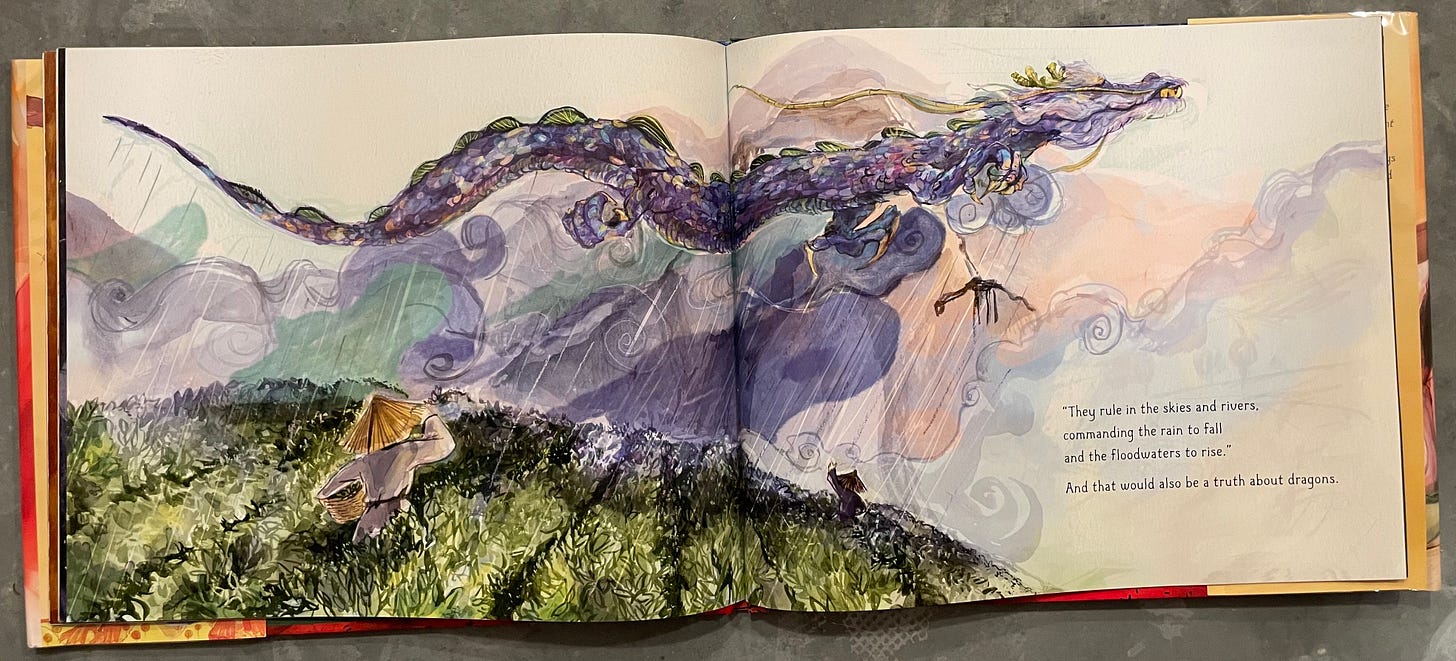

She, too, has a truth about dragons. But it’s different than the last. Her dragons are the ethereal guardians of the East. “They have a body like a serpent, with five claws on each leg, and a flaming pearl embedded in their chin.” Instead of living in caves with hordes of gold, these dragons are creatures of the sky and water, controlling the weather according to their whims.

These dragons are as true as the last set. Neither is superior to the other. Neither is more real. Yet that is not how the world will see it. “Some who cannot travel more than one path may demand that you choose between the clouds and the caves. For dragons cannot dwell in both, they say.”

But bao bei doesn’t need to fall prey to that false choice. “This is the precious secret: Inside your heart is where the two forests meet. Both journeys are yours to take. Both worlds are yours to discover.” And there, on the penultimate page, is bao bei, nestled between both dragons, both worlds. Each is the size of the other. Each bows to his touch. Each gives him ballast.

At the start of the school year, I was all mixed up over whether to send N, our five-year-old, to Hebrew School.

She’s only five -- it doesn’t matter if we wait!

But she’s five -- if we aren’t starting now, when?

It was logic so perfectly circular you’d think I was using a compass.

If only I had that other kind of compass to point the way. My wife didn’t care what I decided; since we chose to raise them in my home court, I had to decide what time the game should start.

I spent months dragging my feet on a decision, hoping that some burning bush would reveal itself and answer the question for me. Alas, deus ex machinas are few and far between these days.

I finally called the neighborhood synagogues, hoping that a good sales pitch would close the deal. But each conversation left me further adrift. How could I send my kid to a synagogue I had no relationship with? How could I let someone else indoctrinate her with religious teachings I’d often disagree with? How could I raise a Jewish kid while raising a secular one?

But I was falling prey to the same false choice the narrator warned bao bei about. I was my own antagonist, demanding that I -- and N -- choose between the clouds and the caves. I was so desperate to pass along my own tenuous balance between Judaism and secularism that I worried my kid would arrive at a different one.

And if she did, what would that mean? That I was raising a kid who was like the kid I was, but not the adult I am. The horror!

There’s a saying in Hebrew that’s always stuck with me: L’dor v’dor, from generation to generation. There’s a power -- a holiness, even -- in the traditions and teachings that are passed down from those who came before to those who come after. It’s a lovely idea, and a worthy ideal. I think I first learned about it in Hebrew School.

Maybe N will learn it too. If so, it’ll be next year. The truth can sometimes take its time before making itself known.

It can sometimes be hard to find a book about diversity that isn't so earnest it hurts. But “The Truth About Dragons” manages to stay light on its feet without losing its sincerity. It’s really one of my favorite kids books. I’ve wanted to write about it since Writ Small started, but I was worried I wouldn’t do it justice.

If you’d like to do the authors justice, you can buy the book here. My usual warning: I’ll get a 10 percent commission if you buy it through that link, so click wisely.

It’s been a while, huh? Welcome to all of you who came from NYMag’s list of the best kids books of the year, which was kind enough to feature my blabbing. I recommended Julie Morstad’s latest, “A Face Is A Poem,” which is as beautiful as we’ve come to expect from her. Longtime subscribers will recognize Morstad from the subject of the first-ever Writ Small, “Today,” which is her ode to how great kids feel when they get to make their own decisions.

If you’re new here, welcome! At this point, this is an extremely irregular -- and increasingly ruminative -- newsletter about all the fun media kids get to take in. The best way to help Writ Small is to tell a loved one about it. If there’s a truth about newsletters, that’s the only one.

Have something I ought to read, play, listen to, or do some other verb with? Let me know in the comments or with this button.

I think I’ll be writing about a board game next. I think I finally found one that was made for kids even though it was made for adults. Talk soon.

Excellent writing as always. It sounds like you and your wife have experienced a shift in how religion plays a role in your family life compared to your own childhood experiences. This is something many people go through as they grow older or as families evolve.Time will tell if my children follow in your footsteps :)